LEra il 25 luglio 1998, a Spilimbergo, quando le note di Fabrizio De André chiudevano la ventesima edizione di Folkest. Mancavano pochi mesi a quel gennaio 1999 che avrebbe lasciato un vuoto incolmabile nella cultura italiana. Eppure, in quella sera d’estate, accadde qualcosa di rivelatore: durante l’esecuzione di “Anime Salve”, le parti originariamente affidate alla voce di Ivano Fossati vennero cantate da Cristiano De André.

In quell'istante, la sensazione fu nitida: se quel capolavoro non poteva essere interpretato da Fabrizio insieme a Fossati, esisteva un unico interlocutore possibile, un’unica anima capace di reggerne il peso e la poesia. Quell’anima era Cristiano, l’unico vero custode di un codice genetico musicale irripetibile.

Limitare la figura di Cristiano De André al ruolo di "figlio d'arte" sarebbe un errore imperdonabile. La sua storia parla di un artista che ha saputo forgiare la propria identità nel fuoco del talento puro. Nato a Genova nel 1962, Cristiano è cresciuto nutrendosi di teatro e musica, diplomandosi al Conservatorio Paganini e dimostrando fin da giovanissimo una padronanza rara degli strumenti: dalla chitarra al violino, dal bouzouki al pianoforte.

Il suo percorso solista è costellato di perle assolute. Pensiamo a “Bella più di me” (Premio della Critica a Sanremo 1985) o a quel capolavoro di rara intensità che è “Dietro la porta”, che nel 1993 sfiorò la vittoria all’Ariston portando a casa i premi più prestigiosi. E ancora l’album “Scaramante” (2001) e la vittoria del Premio Mia Martini con “Invisibili” nel 2014. Cristiano ha dimostrato di avere una voce autoriale potente, capace di graffiare e commuovere con una sensibilità tutta sua.

Dal 2009, questo talento si è messo al servizio di una missione più grande: il progetto “De André canta De André”, ovvero una rilettura vitale, filologica e al contempo innovativa del repertorio del padre. Attraverso quattro volumi discografici e tour costantemente sold-out, Cristiano ha riportato in vita la Storia di un impiegato e i grandi classici, restituendo loro una veste sonora moderna senza tradirne l'essenza profonda.

Oggi, questo viaggio giunge a una nuova, attesissima tappa: il “De André Canta De André Best Of Tour 2026”.

Dopo il trionfo nelle stagioni teatrali, la tournée estiva si preannuncia come uno degli eventi più emozionanti del 2026. A grande richiesta, il calendario si è arricchito di 7 nuove date che porteranno Cristiano a calcare i palchi più suggestivi della penisola.

Sul palco, Cristiano sarà circondato dai suoi "inseparabili" compagni di viaggio: Osvaldo di Dio alle chitarre, Davide Pezzin al basso, Luciano Luisi alle tastiere (già architetto degli arrangiamenti dei primi volumi) e Ivano Zanotti alla batteria. Sarà lui stesso, da virtuoso polistrumentista, a guidare il pubblico tra le corde del violino e del bouzouki, in un percorso che attraversa l'opera omnia di Fabrizio.

Partecipare a una data di questo tour significa immergersi in una materia sonora viva: canzoni impresse nella memoria collettiva che, attraverso le mani e la voce di Cristiano, ritrovano una fiammante attualità. È il racconto di un uomo che vive la musica con la stessa viscerale onestà di chi lo ha preceduto, ma con il passo di chi ha saputo tracciare un proprio, autonomo sentiero.

Queste le date al momento programmate:

10 aprile al Teatro Rossini di Civitanova Marche (Macerata)

14 aprile al Politeama Rossetti di Trieste

16 aprile al Palazzo dei Congressi di Lugano

17 aprile al Gran Teatro Infinity 1 di Cremona

19 aprile al ChorusLife Arena di Bergamo

21 aprile al Teatro Auditorium Santa Chiara di Trento

22 aprile all’E-Work Arena di Busto Arsizio (Varese)

21 maggio al Teatro Augusteo di Napoli

22 maggio al Teatro Team di Bari

22 giugno al Barton Park di Perugia

26 giugno al Teatro Romano di Fiesole (Firenze)

27 giugno all’Anfiteatro Romano di Susa (Torino)

29 giugno a Villa Guidini di Zero Branco (Treviso)

26 luglio alla Musica Arena di Cagliari

27 luglio al Teatro di Tharros di Cabras (Oristano)

8 agosto al Parco di Arenzano - Villa Figoli di Arenzano (Genova)

13 agosto a La Versiliana Festival di Marina di Pietrasanta (Lucca)

I biglietti per tutte le date saranno disponibili su Ticketone e Ticketmaster, mentre quelli per la data di Perugia si potranno acquistare anche su Ticket Italia e quelli per Susa anche su Viva Ticket.

The Heritage of Blood and Sound: Cristiano De André and the “Best Of Tour 2026” Journey

It was July 25, 1998, in Spilimbergo, when the notes of Fabrizio De André closed the 20th edition of Folkest. Only a few months remained before that January 1999 which would leave an unbridgeable void in Italian culture. Yet, on that summer night, something revelatory happened: during the performance of “Anime Salve”, the parts originally entrusted to Ivano Fossati were sung by Cristiano De André.

In that instant, the sensation was clear: if that masterpiece could not be interpreted by Fabrizio together with Fossati, there was only one possible interlocutor, only one soul capable of bearing its weight and poetry. That soul was Cristiano, the only true guardian of an unrepeatable musical genetic code.

To limit Cristiano De André to the role of "son of a genius" would be an unforgivable mistake. His history speaks of an artist who forged his own identity in the fire of pure talent. Born in Genoa in 1962, Cristiano grew up nourished by theatre and music, graduating from the Paganini Conservatory and demonstrating a rare mastery of instruments from a very young age: from guitar to violin, from bouzouki to piano.

His solo career is studded with absolute gems. Consider “Bella più di me” (Critics' Prize at Sanremo 1985) or that masterpiece of rare intensity, “Dietro la porta”, which nearly won at the Ariston in 1993, earning the most prestigious awards. Then there is the album “Scaramante” (2001) and his victory of the Mia Martini Critics' Prize with “Invisibili” in 2014. Cristiano has proven to possess a powerful authorial voice, capable of both grit and profound emotion through a unique sensitivity.

Since 2009, this talent has been dedicated to a greater mission: the “De André canta De André” project—a vital, philological, and innovative re-reading of his father’s repertoire. Through four albums and consistently sold-out tours, Cristiano has brought Storia di un impiegato and the great classics back to life, giving them a modern sonic dress without betraying their deep essence.

Today, this journey reaches a new, highly anticipated stage: the “De André Canta De André Best Of Tour 2026”.

Following the triumph of the theatre seasons, the summer tour promises to be one of the most exciting events of 2026. Due to popular demand, seven new dates have been added, bringing Cristiano to the most evocative stages across the peninsula.

On stage, Cristiano will be surrounded by his "inseparable" traveling companions: Osvaldo di Dio on guitars, Davide Pezzin on bass, Luciano Luisi on keyboards (architect of the arrangements for the first volumes), and Ivano Zanotti on drums. Cristiano himself, as a virtuoso multi-instrumentalist, will lead the audience through the strings of the violin and bouzouki, on a path that traverses Fabrizio’s entire body of work.

Attending a date of this tour means immersing oneself in a living sonic matter: songs etched in collective memory that, through Cristiano’s hands and voice, find a blazing contemporary relevance. It is the story of a man who lives music with the same visceral honesty as his predecessor, yet with the stride of one who has carved out his own independent path.

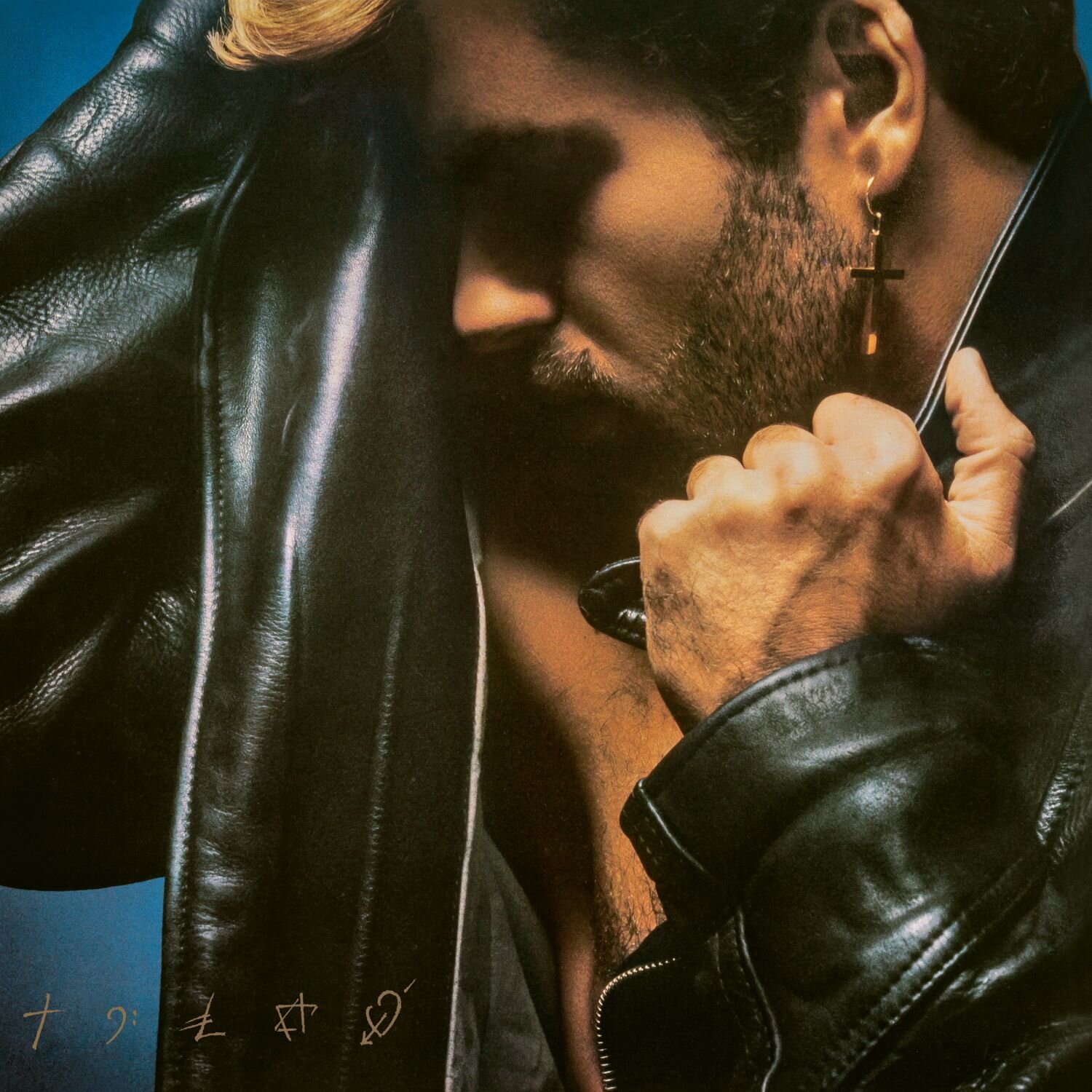

ph Virginia Bettoja

.jpeg)