La mostra “Confini. Da Gauguin a Hopper. Canto con variazioni”, allestita negli spazi restaurati dell’Esedra di levante di Villa Manin, non si trova in un luogo neutro. Villa Manin, con la sua monumentalità misurata e il respiro aperto sulla pianura friulana, è già di per sé un confine: tra storia e presente, tra architettura del potere e spazio pubblico. Qui prende forma una delle esposizioni più ambiziose del panorama europeo recente, inserita nel programma di GO! 2025&Friends, che accompagna Nova Gorica–Gorizia Capitale Europea della Cultura. Un progetto che parla di frontiere senza irrigidirle, di identità senza chiuderle.

Curata da Marco Goldin, la mostra riunisce oltre 130 opere provenienti da musei e collezioni internazionali, ma il dato numerico conta fino a un certo punto. Ciò che resta, fin dai primi passi, è la sensazione di trovarsi dentro un museo ideale, dove l’arte degli ultimi due secoli dialoga per affinità emotive prima ancora che per cronologia.

Il confine, qui, non è una linea da tracciare sulla mappa. È un orizzonte mobile.

Lo si intuisce subito, nella sala introduttiva, dove le superfici profonde di Rothko e le stratificazioni quasi cosmiche di Anselm Kiefer aprono lo sguardo verso spazi interiori prima ancora che geografici. Poco oltre, l’onda di Courbet non separa: avanza. E con Monet, il mare di Varengeville diventa un luogo senza fine, uno spazio che si dilata fino a coincidere con l’idea stessa di altrove.

Il percorso si muove per capitoli, come un racconto corale.

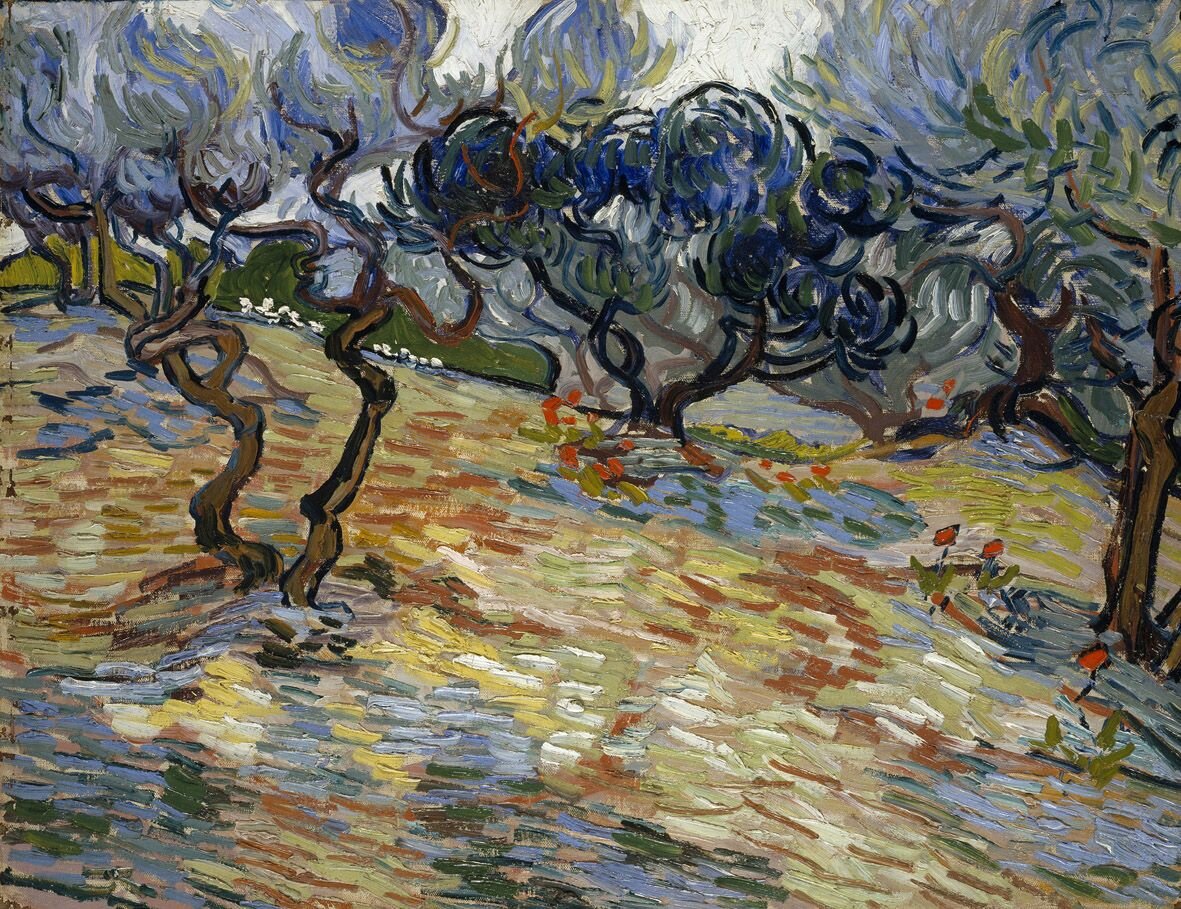

Il primo è forse il più intimo: il confine interiore. Qui l’autoritratto non è esercizio di stile, ma atto di esposizione. Da Van Gogh a Munch, da Gauguin a Kirchner, lo sguardo degli artisti si rivolge verso dentro, cercando nei propri lineamenti una soglia fragile tra identità e smarrimento. I ritratti successivi – da Manet a Modigliani, fino a Bacon e Giacometti – raccontano volti attraversati dal tempo, dalla storia, dalle fratture del Novecento. Il confine, qui, è la pelle.

Poi la mostra si apre, letteralmente, al paesaggio.

Nelle sale dedicate alla pittura americana, il rapporto tra uomo e natura diventa centrale. I grandi spazi della Hudson River School, la luce inquieta di Homer, i silenzi sospesi di Hopper: l’America appare come una terra di passaggio, dove l’orizzonte non è promessa ma interrogativo. Accanto, Diebenkorn e Wyeth modulano il confine tra reale e mentale, tra ciò che si vede e ciò che si intuisce.

C’è poi un capitolo che ha il sapore di una nostalgia universale: la ricerca del paradiso perduto. Gli Eden di Gauguin, le visioni di Cézanne, le vibrazioni cromatiche di Bonnard non sono fughe esotiche, ma tentativi di ridefinire un equilibrio possibile tra l’uomo e il mondo. Non si tratta di andare lontano, ma di guardare diversamente.

In questo dialogo tra vicinanza e distanza si inserisce una sezione sorprendente, dedicata alle xilografie giapponesi. Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige: immagini nate altrove che hanno attraversato gli oceani per influenzare profondamente l’arte europea. Monet e Van Gogh le collezionavano, le studiavano, le amavano. Qui il confine culturale si dissolve, diventando scambio, contaminazione, amicizia silenziosa tra mondi lontani.

Il finale della mostra è un vero e proprio respiro cosmico.

Montagne, mari, cieli: gli elementi naturali diventano luoghi estremi del pensiero. La Sainte-Victoire di Cézanne dialoga con le Alpi di Segantini; i mari di Turner, Courbet e Monet raccontano il confine come attraversamento; i cieli – da Friedrich a Constable, fino a Mondrian e Hopper – segnano il passaggio tra Ottocento e Novecento, tra visione romantica e astrazione. Le Ninfee di Monet, specchio tra acqua e cielo, preparano l’ingresso ai campi di colore di Rothko, dove il confine si fa puro stato d’animo.

Alla fine del percorso, resta una certezza: questa mostra non parla di limiti, ma di possibilità.

Il confine non è più ciò che divide, ma ciò che mette in relazione. Tra culture, epoche, linguaggi. Tra ciò che siamo stati e ciò che potremmo diventare.

In un tempo che alza muri e semplifica le complessità, Confini sceglie la strada opposta: invita a sostare nelle zone intermedie, nei territori di passaggio, là dove l’arte continua a fare ciò che sa fare meglio. Aprire spazi. Dentro e fuori di noi.

INFO UTILI

Orario mostra

da martedì a domenica: ore 9.30 - 18.00

chiuso il lunedì e il 24 dicembre

(vendita dei biglietti sospesa 75 minuti prima della chiusura della mostra)

Servizio prenotazioni e informazioni

(dal lunedì al venerdì: ore 9-13)

TEL 0422 429999

biglietto@lineadombra.it

www.lineadombra.it

Biglietti

Intero € 15

Ridotto € 11 oltre i 65 anni, titolari di Disability Card, FVG Card, Touring Club, FAI

Ridotto € 8 minorenni dagli 11 ai 17 anni, studenti maggiorenni e universitari fino a 26 anni con tessera di riconoscimento

Gratuito bambini fino a 10 anni, accompagnatore di persona con disabilità, giornalisti, membri ICOM, guide turistiche con tessera iscritte all'Elenco Nazionale del Ministero del Turismo

[tutte le tariffe di biglietti, visite guidate e audioguide disponibili su lineadombra.it]

Where Borders End (and Begin Again)

From Gauguin to Hopper, at Villa Manin

“Borders. From Gauguin to Hopper. Song with Variations”, staged in the restored spaces of the eastern Esedra of Villa Manin, is not set in a neutral place. Villa Manin, with its measured monumentality and its open breath over the Friulian plain, is itself a border: between history and the present, between architecture of power and public space. It is here that one of the most ambitious exhibitions in the recent European panorama takes shape, part of the GO! 2025&Friends programme accompanying Nova Gorica–Gorizia European Capital of Culture. A project that speaks of borders without stiffening them, of identities without enclosing them.

Curated by Marco Goldin, the exhibition brings together more than 130 works from international museums and collections, yet numbers only matter up to a point. What remains, from the very first steps, is the sensation of entering an ideal museum, where the art of the last two centuries engages in dialogue through emotional affinities rather than strict chronology.

Here, the border is not a line to be traced on a map.

It is a shifting horizon.

This becomes immediately clear in the introductory room, where the deep surfaces of Rothko and the almost cosmic stratifications of Anselm Kiefer open the gaze toward inner spaces even before geographic ones. Just beyond, Courbet’s wave does not divide: it advances. And with Monet, the sea of Varengeville becomes an endless place, a space that expands until it coincides with the very idea of elsewhere.

The exhibition unfolds in chapters, like a choral narrative.

The first is perhaps the most intimate: the inner border. Here, self-portraiture is not an exercise in style but an act of exposure. From Van Gogh to Munch, from Gauguin to Kirchner, the artists’ gaze turns inward, searching their own features for a fragile threshold between identity and disorientation. The subsequent portraits — from Manet to Modigliani, through Bacon and Giacometti — depict faces crossed by time, history, and the fractures of the twentieth century. Here, the border is the skin.

Then the exhibition opens, quite literally, onto the landscape.

In the rooms dedicated to American painting, the relationship between humankind and nature becomes central. The vast spaces of the Hudson River School, the restless light of Homer, the suspended silences of Hopper: America appears as a land of passage, where the horizon is not a promise but a question. Alongside them, Diebenkorn and Wyeth modulate the boundary between the real and the mental, between what is seen and what is sensed.

There follows a chapter imbued with a sense of universal nostalgia: the search for a lost paradise. The Edens of Gauguin, the visions of Cézanne, the chromatic vibrations of Bonnard are not exotic escapes, but attempts to redefine a possible balance between humanity and the world. It is not a matter of going far away, but of learning to look differently.

Within this dialogue between nearness and distance comes a surprising section dedicated to Japanese woodblock prints. Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige: images born elsewhere that crossed oceans to profoundly influence European art. Monet and Van Gogh collected them, studied them, loved them. Here, the cultural border dissolves, becoming exchange, contamination, a silent friendship between distant worlds.

The exhibition’s finale is a true cosmic breath.

Mountains, seas, skies: natural elements become extreme places of thought. Cézanne’s Sainte-Victoire converses with Segantini’s Alps; the seas of Turner, Courbet and Monet tell of the border as crossing; the skies — from Friedrich to Constable, through Mondrian and Hopper — mark the passage from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, from Romantic vision to abstraction. Monet’s Water Lilies, mirrors between water and sky, prepare the way for Rothko’s fields of colour, where the border becomes a pure emotional state.

At the end of the journey, one certainty remains: this exhibition is not about limits, but about possibilities.

The border is no longer what divides, but what connects. Between cultures, eras, languages. Between who we have been and who we might become.

In a time that raises walls and simplifies complexity, Borders chooses the opposite path: it invites us to linger in intermediate zones, in territories of passage, where art continues to do what it does best.

Open spaces. Inside and outside ourselves.